Category Archives: U.S. Immigration and Refugee Policies

Christmas on the Border, 1929

The poet Albert Rios based this poem on newspaper accounts and personal recollections of residents who were children in Nogales at the time of the event.

1929, the early days of the Great Depression.

The desert air was biting, but the spirit of the season was alive.

Despite hard times, the town of Nogales, Arizona, determined

They would host a grand Christmas party

For the children in the area—a celebration that would defy

The gloom of the year, the headlines in the paper, and winter itself.

In the heart of town, a towering Christmas tree stood,

A pine in the desert.

Its branches, they promised, would be adorned

With over 3,000 gifts. 3,000.

The thought at first was to illuminate the tree like at home,

With candles, but it was already a little dry.

Needles were beginning to contemplate jumping.

A finger along a branch made them all fall off.

People brought candles anyway. The church sent over

Some used ones, too. The grocery store sent

Some paper bags, which settled things.

Everyone knew what to do.

They filled the bags with sand from the fire station,

Put the candles in them, making a big pool of lighted luminarias.

From a distance the tree was floating in a lake of light—

Fire so normally a terror in the desert, but here so close to miracle.

For the tree itself, people brought garlands from home, garlands

Made of everything, walnuts and small gourds and flowers,

Chilies, too—the chilies themselves looking

A little like flames.

The townspeople strung them all over the beast—

It kept getting bigger, after all, with each new addition,

This curious donkey whose burden was joy.

At the end, the final touch was tinsel, tinsel everywhere, more tinsel.

Children from nearby communities were invited, and so were those

From across the border, in Nogales, Sonora, a stone’s throw away.

But there was a problem. The border.

As the festive day approached, it became painfully clear—

The children in Nogales, Sonora, would not be able to cross over.

They were, quite literally, on the wrong side of Christmas.

Determined to find a solution, the people of Nogales, Arizona,

Collaborated with Mexican authorities on the other side.

In a gesture as generous as it was bold, as happy as it was cold:

On Christmas Eve, 1929,

For a few transcendent hours,

The border movedOfficials shifted it north, past city hall, in this way bringing

The Christmas tree within reach of children from both towns.

On Christmas Day, thousands of children—

American and Mexican, Indigenous and orphaned—

Gathered around the tree, hands outstretched,

Eyes wide, with shouting and singing both.

Gifts were passed out, candy canes were licked,

And for one day, there was no border.

When the last present had been handed out,

When the last child returned home,

The border resumed its usual place,

Separating the two towns once again.

For those few hours, however, the line in the sand disappeared.

The only thing that mattered was Christmas.

Newspapers reported no incidents that day, nothing beyond

The running of children, their pockets stuffed with candy and toys,

Milling people on both sides,

The music of so many peppermint candies being unwrapped.

On that chilly December day, the people of Nogales

Gathered and did what seemed impossible:

However quietly regarding the outside world,

They simply redrew the border.

In doing so, they brought a little more warmth to the desert winter.

On the border, on this day, they had a problem and they solved it.

The poet resists any social commentary in describing his poem’s genesis. It appeared, however, as the Academy of American Poets’ “Poem of the Day on December 22, 2024 a month after the U.S. election of a viciously anti-immigrant, white supremacist President. Like other memorable poems, it celebrates the best of human nature and defies any attempts, even by the most powerful, to deny, contradict or pervert the good within each of us. We celebrate today the vision and courage of the “officials” of Nogales with the hope that we may individually and collectively open ourselves to the opportunities in these times to move borders. For the sake of the children in and around us.

Rios commented on his poem, “I didn’t live through the Christmas of 1929, but growing up in Nogales, the border was always there—constant, imposing, dividing and connecting at the same time. This poem reflects on a story from before my time, when the border wasn’t just a barrier but something that became a solution. It tells of a community that, for one Christmas, chose unity over division, moving the line in the sand to bring joy to children from both Nogales, Arizona, and Nogales, Sonora. Growing up with the border always in sight, this story resonates deeply for me—proof that even in separation, people’s determination can make the impossible happen.”

“Make American White Again”

The U.S. economy has long relied on immigrant labor in its growth. The United States is a nation of immigrants. The 19th century transition from an economy devoted to agriculture to a modern industrial system funded by agricultural produce depended on the import of immigrants, with Germans and the Irish leading the way. Along with their essential labor for the new manufacturing sector and the expansion of farming, their arrival and that of immigrants after them brought deep political division reflecting the conflicts in work places and neighborhoods. Charismatic personalities have for two hundred plus years made political careers out of those divisions. Using the tools of distortion, lies, religious differences and buffonery, nation-wide political movements have been created and the nation’s ethnic divisions deepened.

The U.S. Civil War resulted from decades of simmering conflict over the proper role for the African immigrant brought to these shores as slave labor. Sacred texts dated as two millenia and more in origin were interpreted as assigning back breaking labor in fields and estates to the African sold as a slave. Low to no wages producing lucrative crops, cotton especially, for the world made the southern U.S. the supplier of much of the capital for the new nation’s financiers of south and north.

Angry debate over the causes and meaning of the Civil War continues today. Our most hallowed symbol of the United States as a welcoming refuge, the Statue of Liberty, was subjected to controversy and opposition in its creation one hundred fifty years ago. The Frenchman who created the original design saw the Statue as a celebration of the abolition of slavery with broken shackles to be draped from Liberty’s left hand. But to avoid the protests of former slaveholders and their supporters, who portray slavery as an idyllic era, the shackles now are partially hidden by her gown’s layers of folds and are barely visible from the ground level promenade.

America’s long history of anti-black racism and professed white superiority makes the nation’s response to the rise in the world’s immigrant population especially challenging, emotionally and politically. In the comprehensive study of world immigration by the U.S. Pew Research Center, it was found that one out of five immigrants in the world live in the U.S. While we now have far more immigrants and children of immigrants inside our borders, the majority of our more recent arrivals are persons of color, not the white adults and children from Europe and Scandanavia of the 19th century. As late as 1920, most of the newly arrived came from Italy and Germany, with Canada a distant third. Much of the shift to the immigration of persons of color has occurred since passage of the 1965 immigration reform. In 2022 the nation’s largest immigrant populations hailed from Mexico and India.

The 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act supported the shift in the origin of immigrants. Eliminating quota provisions favoring immigration from Europe, it gave preference to skilled workers and immigrants from anywhere with family members already settled in the U.S. The Act thus contributed to the rise in immigrants of color primarily from the earth’s southern hemisphere and a considerable increase in the numbers of immigrants in the country.

In the fifty years after passage of the 1965 law there were a total of 72 million immigrants and their children who came to the “land of freedom”. They accounted for 55% of the growth in U.S. population and Pew researchers project they will make up 88% of the growth from 2015 to 2065 when the nation will number 441 million persons and no ethnic group will constitute a majority of the population. Whereas non-Hispanic whites totaled 84% of the U.S. population in 1965, Pew studies project they will number 46 % in 2065. Continuing immigration from Latin America will make Hispanics 25% of the population and by 2065 14% of the nation will be Asian in origin.

Given voting trends in recent elections showing Hispanics favoring Democrats, the Republican party leadership has been particularly concerned by the dizzying increase in their numbers. Their current response is to support with near unanimity a candidate for U.S. President who has made the country wide settlement of immigrants of color the focus of his campaigns. His primary policy proposal, virtually his only concrete pledge, is to return two million recent immigrants to their countries of origin. The Republican candidate has repeatedly characterized Democrats’ relatively lenient response to the shift in immigration from the southern hemisphere as admitting “criminals and rapists” into our communities. In this month’s debate between the Democratic and Republican candidates for President, regardless of the question at hand Trump returned again and again to foreign nations sending their most dangerous citizens across our borders.

Trump’s history of racist rhetoric and commentary reveals the underlying message of the campaign slogan “Make America Great Again” for his 2016 and 2024 campaigns for President. A Wikipedia article on the phrase reports the candidate still denies the influence of Ronald Reagan’s successful 1980 campaign use of “Let’s Make America Great Again” as a slogan. Trump does outdo Reagan in disclosing the covert intent of its use as “Let’s Make America White Again”.

His outrageous claim that Haitians, migrants from one of the “shithole countries”, are eating the pets of residents of Springfield in the crucial State of Ohio may, however, have back fired. Not only did the city’s top administrator deny the report which Trump culled from an extreme racist’s social media posting, the town’s populace has been patronizing the Haitian restaurants as never before and emphasizing their new businesses and Haitian labor as vital to the growth of the local economy.

While the heavily Republican area may still vote for Trump in this year’s election, the recent affimation of the Haitian immigrants by many Springfield residents illustrates the central question raised by the candidates. Will the U.S. citizenry finally signal their embrace of the nation’s image as a haven of welcome for people of any and all ethnicities? Or will it step up its effort to hold back the migration patterns of our modern era in a futile effort to return the U.S. to a time when its white population were a majority. Representing the nation’s ideals as embedded in its history of immigration moving the economy, the culture, the community life forward, the opposition Democratic Party candidate is a woman of mixed Asian and African ancestry. If Harris’ Democratic Party is able to safeguard a victory in the upcoming election, the outcome will mark the nation’s progress to becoming a true “multi-racial democracy”.

Erasing Borders in Chiapas

I’ve just returned from a week long stay in Chiapas, the southernmost State of Mexico. I went with six other adults from my Peace Christian Church (United Church of Christ/Disciples of Christ) in Kansas City. We did not go to “help” those who hosted us in any substantial, tangible way. On what can be best described as a “decolonizing mission” pilgrimage, we went to learn about the legacy of Spanish seizure of land, suppression of indigenous culture and the native resistance to the foreign presence and influence in Chiapas. These all remain sources of the multiple conflicts Chiapas has experienced in recent years. In tandem with the oppression of the indigenous people, religious differences have been used by the Mexican State, foreign corporations and the cartels to stir conflict among the indigenous Mayan peoples and others in the State.

One of our partner agencies in global mission today hosted our delegation and introduced us to how they work for inter-religious and inter cultural understanding, reconciliation and peace. The INESIN staff represent and interpret well the diverse cultures of the Mexican State of Chiapas. There is jPetul, a former Catholic priest of Lacandon Mayan origin, who instructed us in the meanings and practice of creating a Mayan sacred altar. His spouse is a former nun led us one morning in moving through the Catholic daily meditation on “the liturgy of the hours”. In his welcome and introduction to the history of INESIN, the director told us he serves too as pastor of a Protestant church in the Chiapas capital, Tuxtla Gutierrez. We worshipped there on the Sunday of our week long stay.

We learned about the sources of the multiple conflicts in Chiapas after the Conquest through three hundred years of Spanish colonial rule from another partner of our denominations’ “Global Ministries”. Sipaz (https://www.sipaz.org) presents workshops designed to free and protect the population from Chiapas’ cycles of violence while other programs aim to educate and encourage advocacy among foreign visitors. The Sipaz director for the past 20 years is a woman who described recent political and economic developments as well as Chiapas’ historical context.

Marina noted that the trafficking in migrants through the State of Chiapas and on to the U.S. is now largely controlled by leading Mexican cartels, formerly primarily engaged in the drug trade. Lax security and immigration enforcement at the Guatemalan border reflects Mexican Government border policy, funded by the U.S., of interdicting undocumented migrants on the roads of Chiapas. The immigration attorney among our pilgrims had prior to our trip discovered that the Guatemalan State and one of the country’s leading banks have profited from their fellow citizens’ migration. Failure to repay loans for the U.S. journey results in loss of a Guatemalan migrant’s land.

Another grim aspect of the situation is the targeting of older children and youth in recruitment by the cartels and local militias. We observed the third of our denominations’ partner agencies in San Cristobal working with poor children, of Mayan families, who are encouraged and trained by Melel Xojobal (“true light” in the Tzotzil Mayan language) to value their earning potential outside the cartels’ grip and to defend their human rights. Melel Xojobal (https://www.melelxojobal.org.mx/ ) meets and organizes groups of children at the markets. A recent series of protests by Melel children won expansion of bathroom facilities in the City’s largest markets.

With a crammed schedule on little sleep, I took a break mid-week and missed the trip to the Guatemalan border with stops at two Precolumbian centers of Mayan culture and religion. The recently excavated ruins were built and flourished during what some scholars refer to as the “Dark Ages” in Europe. Between the third and tenth centuries A.D. the Mayans made their most significant contributions to the advance of our species. Viewing the vestiges of the Mayan legacy in the early 1500’s, and judging them as “pagan”, the Spanish missionaries and soldiers destroyed all they could identify as Mayan. Of the hundreds of books written on scrolls of bark by Mayan scribes, only three remain to instruct us on Mayan civilization.

Oppression of the Mayans under Spanish colonialism and decades of discrimination have led to speculation, even at present, that the magnificent Mayan temples, observatories and stone sculptures were created by members of Atlantis’ lost continent or another fabled people. Sadly there are Mexicans who still hold, along with their neighbors in the U.S., demeaning views of the indigenous people of their country. Anyone today who spends time in Yucatan or Chiapas or one of the four Central American nations inhabited by Mayan peoples today cannot question the resemblance of the figures depicted on the ancient sculptures and the indigenous people around them.

After visit of a great Mayan city of the past like Palenque in Chiapas, one is moved to think that the capacity of over 5 million Mayans to have survived centuries of exploitation and genocidal attack is in itself a remarkable achievement. The leading U.S. scholar of Mayan history and culture, Michael Coe, attributes the endurance of the Mayan peoples to three factors. In the ninth edition of his book The Maya he writes,

“What has kept the Maya people culturally and even phsically viable is their hold on the land (and that land on them), a devotion to their community and an all-pervading and meaningful belief system.” Coe then comments, “It is small wonder that their oppressors have concentrated on these three areas in incessant attempts to exploit them as a politically helpless labor force.”

I had in a 1980 journey through Chiapas been able to spend a day at Palenque which is touted by many visitors as the most dramatic and beautiful of the Mayan centers revealed to date. Our hosts advised against a visit as there is now a relatively insecure and substandard 200 km. plus route from San Cristobal to Palenque. Comparable in my mind to the majesty and achievement represented by the French cathedrals of Mont St. Michel and Chartres, an experience of Palenque insists that we revisit our stereotypes of the Mexican people and the Mayans of Mexico in particular. After taking in Palenque one cannot fail to be amazed and moved that the waiter serving you dinner or the woman cleaning your room comes from an ancestry that created such monumental beauty.

B.Traven’s and Our Struggle to Be Human

There were some years in the 1930’s when B. Traven was the most widely read fiction writer in the world. Today, his many novels and collections of stories have exceeded 25 million in sales and been translated into more than 30 languages. In spite of his huge legion of readers, his biography and even his name continue to be debated. After his death, in his late 70’s? or late 80’s?, in 1969, his first and only wife Rosa Elena Lujan, suggested “He believed that individual stories are not important until they flow into the collective life”. She elaborated that he was “very much in love with communal life and communal thinking”.

Lujan, translator of many of his books into English, also revealed that Traven had indeed been the German revolutionary Ret Marut. Condemned to death by firing squad in 1919 in Munich, the former communications officer of the Bavarian Socialist Republic escaped from his captors and sought refuge on a freighter that took him, an undocumented man claiming to be born in the U.S., around the world. We know for certain that for more than five years, he was a man without a country.

In 1925 he chose life on land in México and jumped ship in the northern port of Tampico. Two novels that he had likely written while at sea were published a year later in Germany by the author B. Traven. The Death Ship tells of an undocumented sailor and his mates exploited ruthlessly by the captain and owners of a global freighter. Gerald Gales, the sailor, is also the protagonist of The Cotton Pickers, first titled The Wobbly, who tells his fellow farmworkers that he identifies with the Wobblies (Industrial Workers of the World). Wobbly publications and artifacts remained stored among his personal items to his death.

Not surprising that many literary critics as well as readers have described Traven as a proletarian writer. This is true to a limited degree but there is a larger view of the man’s work and his life as a whole. I prefer thinking of him as an internationalist with exceptional compassion for people of all nationalities, tribes, and cultures. And a man with an unsurpassed talent for expressing that compassion through tales set in the highly diverse environments of México, his adopted country. A foremost example of what I see as his “internationalist” affiliation is found in his dedication of The Bridge in the Jungle:

“To the mothers

of every nation

of every people

of every race

of every color

of every creed

of all animals and birds

of all creatures alive

on earth

This begins the story of a mother’s and her Chiapas villagers’ anguished search for her exuberant pre-teen son. The same “internationalist” devotion can be found in most of Traven’s fiction. While exploitation of the workers by the man with capital is present in his best known book in the U.S., The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, other non-proletarian specific themes prevail. The grizzled old prospector cures an Indian on the way to the “treasure” and finds his place among his patient’s people. Thompson renounces the pursuit of great wealth for the envisioned peace with a loving wife and small farm in the Midwest. And Dobbsie, who resembles Traven the most, is tamed through the grueling pilgrimage to more knowledge of himself.

The passion of celebrating the worth and dignity of every human being drives Traven’s creativity. The writer’s utopian dream was of a world where the work of the typesetter, the secretary in the publisher’s office, the mailroom clerk, and the writer were all equally valued. What sets Traven apart from other modern writers in the hundred years since his fiction first appeared is his embrace and affirmation of all peoples and cultures. While his focus continued to be on the surviving Mayan cultures and people of Chiapas, southern México, he didn’t romanticize or set them apart from other “pre-modern” cultures or our own today. Traven lived off and on in Chiapas for a total of at least two decades and his ashes were scattered over the jungle there.

In her introduction to The Kidnapped Saint and Other Stories Mrs. Lujan wrote of his love for Chiapas. “Traven went to the Indians of Chiapas as a brother, a friend, and a comrade, not as most outsiders did, to steal from or exploit them.” She heard from her husband how he lived among them: “At night Traven slept on the hard ground with only his serape wrapped around him. In the morning he rose early and ate tortillas and chili with them.” She notes that her husband had a gift for languages and could converse in several Mayan dialects.

Why B. Traven spurned the great wealth and fame that would have come from his life work he explained in 1929. Writing a German professor who lectured on his books, Traven wanted it understood that “I do not want to give up my life as an ordinary human being”. To do so would have undermined his aim to “do my part to get rid of all authorities and the veneration of authorities so that every man can feel stronger in the knowledge that he is absolutely as indispensable and important for the rest of humanity as every other person no matter what they do.” Our duty as human beings was to “serve humanity according to our understanding and capacity, to lift up the lives of others, bring them more happiness and direct their thoughts to meaningful goals of life.” Forty years later, at his death, Traven could look back on a lifetime of remaining faithful to this goal. B. Traven, presente!

Building Community For a New World

There were networks of trade that fed the Native American people in the United States long before the arrival of the first European settlers. Their corn, a staple for them, came from the South, Mexico and Guatemala, before they learned to grow the crops for themselves. Several varieties of bean imported from the South were also added to their diets. The hunter gatherer people of the U.S. imported from the same areas cacao, peppers, squash, sweet potatoes, and the tomato. And tobacco was introduced along with the food crops.

According to the theories of the late Russian geneticist N.I. Vavilov, most of the world’s basic food plants originated in a relatively few places on the planet, most of them close to the equator. Experts in this field call these places Vavilov Centers to commemorate their importance to our world.

The diets of the first European settlers on the Atlantic coast benefited greatly from the well established trade networks with the South. Had they been restricted to consumption of what were native plants only, they would have had to make do with the sunflower, blueberries, cranberries and the Jerusalem artichoke. Development of trade between the settlers and the “Old World” sparked cultivation of almonds, carrots, flax, hemp, lentil, onion, peas and wheat from Central Asia. Asparagus, beets, hops, lettuce and olives originated in the Mediterranean. The settlers’ tastes governed which of the plants were favored and cultivated more widely. “American cuisine” largely relied on what were “non-native” crops.

In the last 50 years diets in the U.S. have been transformed not by imports of new crops so much as by the addition of new dishes introduced by immigrants to the country. Mexican restaurants and recipes have swept the country. When I returned from a year in Guadalajara in 1980 I had to search for a Mexican restaurant in U.S. cities I visited. Today our favorite “neighborhood” take out meals in Kansas City are from a Mexican restaurant and a Palestinian restaurant/grocery store less than two miles from home. Hummus and the fresh pita bread have become staples of my diet. A primary attraction of most U.S. urban centers today is the variety of ethnic restaurants opened by immigrant families across the country.

For many residents of and visitors to our urban centers the diversity of ethnic foods offered is part of the appeal. Any major city stages an international feast every night. In some venues the food is accompanied by music and/or dance enhancing the flavors of the culture. Beyond the food, music and art work decor, there is, however, little exposure to the culture. In most restaurants, we eat at separate tables. That might change though.

Someone asked Myles Horton at the beginning of the Civil Rights era how he was able to get whites and black residents of the South to meet and learn together at the Highlander Center. Horton quickly replied, “First, you set the table; then you call everyone to dinner and serve the hot meal.” We can imagine one long table for everyone gathered at Highlander. This story reminds me of my own experience in New York City in the mid-1960’s. One of the most popular restaurants in Manhattan’s Little Italy was Mama Leone’s. You usually had to wait for places to open up but you were seated at one of the two or three long tables with strangers already enjoying their pasta fagioli and lasagna. I never left the place without a happy stomach and a full spirit.

May we all find places in the future where new dishes are enjoyed and the tables are long. And may the delight in sharing a meal with people who are strangers lead to thanksgiving for and celebration of the diversity of food and cultures in our lands today.

What Hawaii Had to Teach Us in Our Visit

During my second visit on the “Big Island” of Hawai’i, in the checkout line at the Malama Market in Honoka’a the cashier addressed me as “Uncle”. It was not the first time a young person had honored me with this traditional Hawaiian sign of respect. But as a reminder that wearing a face mask was still required in the grocery store, it made a deeper impression. I retrieved a mask from my back pocket and put it on before removing the items from my basket. After I thanked the young woman for this gentle nudge, my gratitude grew. Like the colorful bird species, the abundant growth of mango, papaya and other tropical fruits and trees, this custom of calling an elder “auntie” or “uncle” had captured and filled me.

My delight had nothing to do with removing my identity as a “foreigner”. I would always remain a “haole” in the land and culture of the native Hawaiian. It was like the customary welcoming to Hawaii another kind of lei showing that the native traditions include the embrace of persons wherever they come from. You cannot spend a day on the Island of Hawai’i without the recognition that you are not on the North American continent. And that you are and will forever be a “haole”.

Having returned to Kansas City, I am even more grateful for our friends who are natives of the “Big Island” and whose hospitality falls on us like the soft rain of the rainforest surrounding their birthplaces near Honoka’a. I understand better the pride displayed by the son of our closest Hawaiian friend who as a three or four year old, though born in California, protested to my wife Kate, “I am not an American, am I Mom? I’m Hawaiian.”

I also now appreciate more our role as “hanai” or “adopted” grandparents of this child now preparing for college on the “mainland”. When my wife introduced ourselves at a Sunday worship service in Honoka’a as Gabriel’s “hanai” grandparents, expressions of approval were quietly uttered by the congregation. From now on, all our efforts to encourage and support the young man’s growth will be not just out of love for him but will also stem from the desire to honor the Hawaiian tradition and our identity as his “hanai” grandparents.

How sad and unfortunate that so many of our would be “leaders” in the mainland U.S. portray the nation’s increasing population of foreign born persons as a loss for the heirs of white settlers. How could someone be persuaded to view immigrants as posing a threat when their contributions are so many and so obvious? Against all the white supremacist theories and arguments we can all learn from and enjoy the embrace of other cultures in the history, language and customs of native Hawaiians.

As an example, there is much more to the meaning of “aloha” than our “hello” and “good bye”. After my recent visit, I now associate the Hawaiian language’s “aloha” with the Indian custom of greeting and leave taking with “namaste”. My favored interpretation of that Hindu greeting and leave taking is “the divine in me recognizes the divine in you”.

Feeding the Wolf

In a blog dedicated to “erasing borders” I want to address what force or forces serve to defend and strengthen national borders and border enforcement in the world. Now is the time because increased migration of threatened people across borders, “free trade” agreements, new technologies, and more travel (among other factors) all call for easing traffic across borders.

It is a confounding paradox for citizens of the U.S., especially for those born in the country with a single cultural identity, to delight in being surrounded by persons of other cultures while the politics and political economy of the country fosters suspicion and enmity of other nations and cultures. How could it be that a nation whose ideal self image, the ideal we grew accustomed to celebrating in our lives and in the life of the nation, has been that of a country leading in welcoming immigrants, how could it be that the same nation remains deadlocked on immigration reform for 35 years and focuses on combatting one enemy overseas after another?

Any attempt at a satisfactory answer to this question must consider some indisputable facts too long ignored. For anyone following the news casually, regardless of the news source in this country, we are aware of the U.S. emphasis on national defense and security. From the Defense Department budget, to television ads selling insurance for veterans, to conversations with those whose loved one is serving in the military, to statistics on the U.S. military’s footprint in over 80 other countries, we know this country is exceptional in equating military might with power and security.

What we don’t know and seldom talk about in our public forums is the effects on our loftiest ideals of our emphasis on preparation for war and conflict. What we also don’t think or talk about much in our civil dialog is the interaction between production of weaponry and the health of our economy.

Histories of California’s economy all point to the manufacture of aircraft as leading the way in the State’s growth. Its long Pacific sea shore has seen the rise of some of the largest and most important military bases during and following WW II. When a few bases were closed in the 90’s, and major aircraft production sites shut down, there was deep concern about what would replace them in the economies of the local communities and the State as a whole. Today the strength of California’s economy should assure us that a transition from an economy relying on defense expenditures can benefit a state’s population

Following the “Great War”, as many in the U.S. now term WW II, the late Prof. Seymour Melman devoted his research and writing to bringing to light the potential boost of the national economy with a conversion from defense production to production of “things that make for peace”. Despite his sterling credentials as a Columbia PhD in economics and his teaching at the same university until 2003, there has been little support for Melman’s views except among left wing intellectuals and peace organizations. He continues to be a “voice crying in the wilderness” in the political and economic discussion in this country.

Yet Melman’s case for such a conversion of the U.S. economy is more relevant today than ever. In a 1990 interview with journalist Bill Moyers, Melman noted “there’s no mystery in the shabby railroads, the broken bridges, the unpaved streets, the wrecked buildings, the absence of adequate housing, the aging character of the industrial equipment.” There is today more decline in U.S. manufacture of goods used by or benefiting individual consumers. With 46 per cent of U.S. production equipment devoted to manufacture of weaponry in the mid-1980’s, Melman urged us to consider the impact on employment in manufacturing, on industrial research and development, on worker productivity and on wages among other measures of a healthy economy.

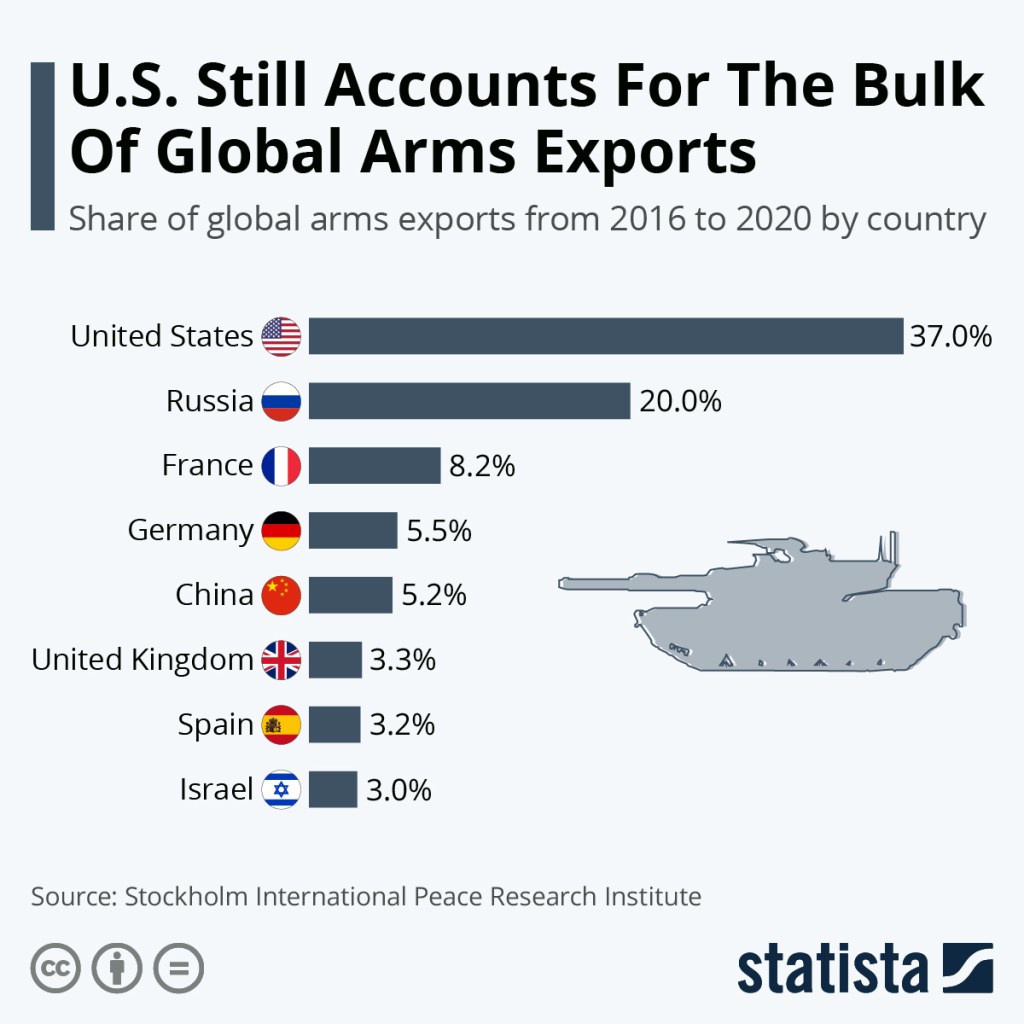

In highlighting the economic effects of this country’s production of goods individuals do not consume, Melman’s views also raise questions about the effect of arms production and sales on U.S. policies as a superpower. How do arms sales abroad, we accounted for 37 % of the world total sales in 2020, affect our foreign policy? What about the influence of the arms industries (the Lockheeds, Raytheons, General Dynamics, etc.) on the military establishment strategies and our perpetual wars? What are the costs to the nation’s ideals and self image of selling vastly more weaponry than any other nation in the world? Finally and most urgently in our time, how does our focus on defense and arms production handicap our capacity to lead in renewable energy production and innovation?

While controversy rages in our politics over what to do about the climate crisis worldwide, the response to a global pandemic, and how to move toward a healthy multi-racial society there is little conflict in our politics on defense and security issues. Consensus of the two parties on expanding our military and waging war for international conflict resolution seems guaranteed.

A few years ago a Cherokee Indian fable was widely shared. A wise grandfather advises his grandson that there are two wolves inside all of us. One of the wolves is characterized by anger and fear and the other wolf is accepting and loving. The two wolves fight within each of us. So the grandson asks which wolf finally wins and the grandfather replies, “The one you feed will win”. Despite its lofty ideals and grand achievement in the past, does anyone doubt which wolf the U.S. continues to feed today? What will be the consequences for the nation if the wrong wolf wins the battle within us? What will be the consequences for the world?

Migrant Farmworker Success Stories

You’ve been picking onions this summer. Now someone is taking you to pick peaches and apples somewhere. You only know it will be as hot as where you picked the onions. As soon as it begins to cool off, the apples will be picked and your visa will expire. Then they take you back to the border crossing.

For three or four years the recruiter returns to take you to the same fields. The orchard owner notices and likes your work. He asks if you’d like to work year round and become a “crew boss”. The pay he mentions exceeds what you ever imagined making.

You are one of the lucky ones. In 2020, there were 213,000 H2A temporary agricultural worker visas issued by the U.S. In 2007 there were 51,000. Ninety three per cent of the 2020 visas were awarded to Mexican farmworkers. Estimates of the total U.S. agriculture work force vary widely but most range from 2 to 3 million workers, both seasonal and year round.

Even as a H2A visa holder you are not eligible for most government services. Your housing is in a field camp, but you are responsible for your health care, sick pay and food when natural disasters or pandemics prevent you from working. Whether you receive any help with these is up to the owner of the fields. That is unless there is an organization like the Migrant Farmworker Assistance Fund (MFAF) of Kansas City.

Since its founding in 1984, the MFWAF has been the catalyst for creating a health clinic and a Head Start early childhood education center. MFAF staff and interns have offered farmworker children after school and summer camp programs, assisted with scholarships and counseled families on opportunities for a college education. Just retired from 39 years as a Legal Aid attorney, the organization’s founder and leader is Suzanne Gladney.

For workers in the orchards and packing sheds an hour drive east of Kansas City, Suzanne’s legal support has been vital. Adults and family members rely on her to negotiate the byzantine and dysfunctional U.S. immigration system. The MFAF legal and other services help ease some of the farmworkers’ transition to year round employment and residency in the U.S..

Many of the workers are from rural Mexico and have never seen a doctor before going to the clinic organized by MFAF. “They say,” Suzanne recently told me, “why go to a doctor? You don’t think I’m dying do you?” Health services and educational opportunities available to workers and family members compensate for the hard labor, long hours, low pay and often poor housing afforded the men and women.

Thanks to MFAF guidance and encouragement, many farmworker children have graduated from nearby high schools and community colleges. A few have continued their studies and one young man is now studying for a PhD at Catholic University in D.C. He completed his Masters’ degree in Memphis where he met his wife-to-be, the principle dancer with the Memphis Ballet. George is one of many success stories of MFAF’s contributions to the lives of Kansas City farmworkers.

In our meeting, I asked Suzanne what keeps her going in her work to maintain funding, guide staff and volunteers, improve living conditions for farmworkers and their families and struggle with U.S. immigration policies. “It’s the stories that help keep me going” she quickly replied.

What We Need

Nov 3

Posted by erasingborders

Until the election this year, no U.S. Presidential candidate has identified so many enemies within the nation whom we should fear. The Republican Party’s candidate for President has made, as in 2016, purging of immigrants within our borders the foremost plank of his policy platform. But they are not the only group targeted for condemnation and reprisals. His opponents in 32 felony cases in which he has been convicted have now also been put on notice. Media outlets intent on lifting the veil of lying, depravity in relationships with women, violation of business contracts and attack dog strategy in multiple court cases, any persons or group publicizing the truth of his grotesque mendacity may expect reprisals.

Although he has been classified as a would be dictator. a leader in the mold of other authoritarian rulers today and in the past century, an accurate assessment of his biography of misdeeds may require a comparison with figures farther back in history. My own search for a true match has been prompted by the following poem of David Budbill:

“The emperor

His bullies and

Henchmen

every day

Terrorize the world

Which is why

Every day

We need

A little poem

Of kindness

A small song

Of peace

A brief moment

Of joy

– Written by David Budbill in 2005. Budbill was posthumously named “The People’s Poet of Vermont” by the Vermont legislature.

Contemplating the possibility of this nation elevating a depraved egotist to our highest office the Book of Psalms gave voice to what I felt. Here in Psalm 5, written over 2500 years ago, I found an apt description of the man who threatens to become the President of our formerly united States.

“There is no truth in their mouths;

their hearts are destruction;

their throats are open graves;

they flatter with their tongues.

Make them bear their guilt,

O God:

let them fall by their own

counsels

because of their many

transgressions cast them

out,

for they have rebelled against

you.

Those are verses 9 and 10 of Psalm 5, in the New Revised Standard Version translation of the Hebrew Bible. Psalm 133 suggests a source for the “brief moment of joy” for our “every day” as Budbill calls for in his poem “What We Need”.

“How very good and pleasant it is

when kindred live together in

unity!

……..

For there the Lord ordained his

blessing

life forevermore.”

Those are verses 1 and 3b of Psalm 133 in the NRSV translation.

We in the U.S. are blessed by the presence of people from many of the world’s nations who have chosen to make this nation their home. They come in many colors. They come speaking many languages, eating a delightful variety of foods, following many different customs. We encounter them as our yard tenders, bricklayers, journalists, tree trimmers, nurses, meal servers, bus and truck drivers, long term care givers, crop harvesters, doctors, shop owners and clerks and public servants. Every day most of us have the opportunity to show gratitude for their presence and their service. Every day we can all share with them a “brief moment of joy” with a smile, with words of kindness, with words of thanks.

Posted in Global Economy, Interfaith Relations and Politics, Solidarity, Community and Citizenship, U.S. Immigration and Refugee Policies, U.S. Political Developments

6 Comments

Tags: A would be emperor of the U.S., David Budbill, Growing diversity of U.S. population, The Psalms' commentary on the 2024 U.S. election